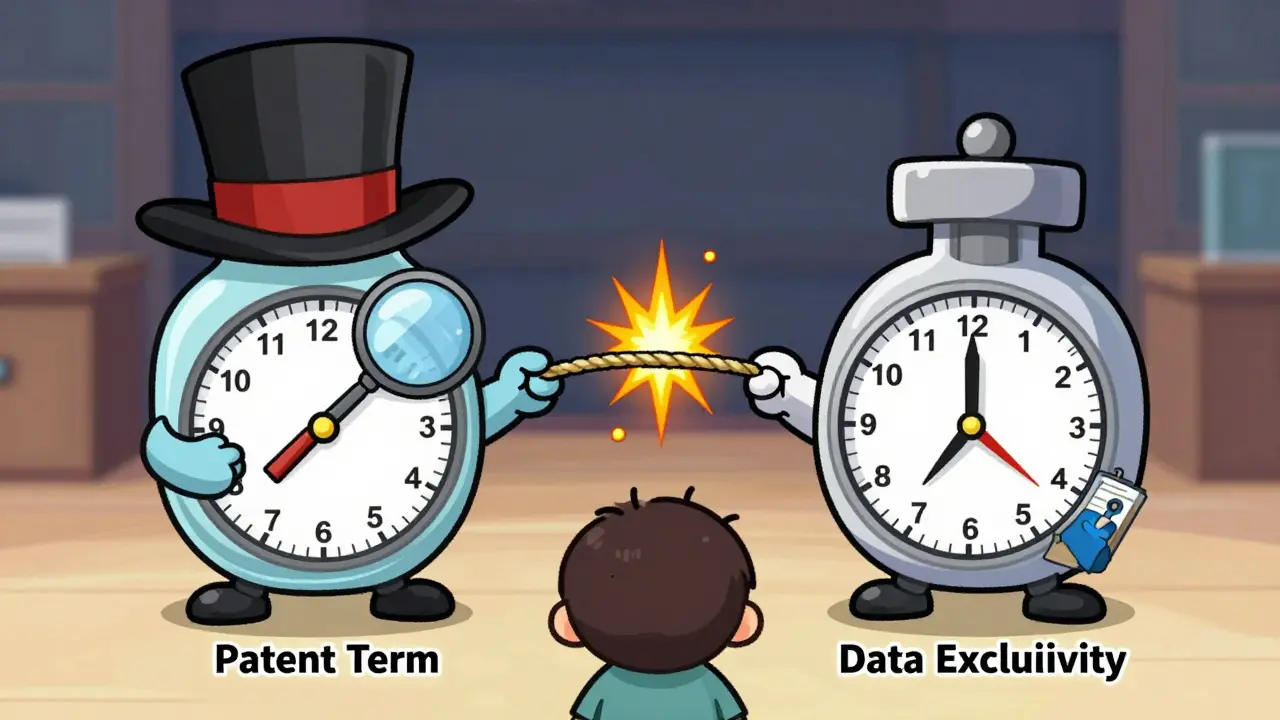

When a pharmaceutical company develops a new drug, it doesn’t just get one layer of protection - it gets two. And if you don’t understand the difference between patent exclusivity and market exclusivity, you’re missing half the story behind why some drugs cost so much and why generics don’t show up right away.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Shield

Patent exclusivity comes from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) a federal agency that grants patents to inventors. When a drug company invents a new chemical compound, a new way to make it, or a new use for an old one, they can file for a patent. This gives them the legal right to stop others from making, selling, or using that invention - for up to 20 years from the date they filed the patent.

But here’s the catch: that 20-year clock starts ticking the day the patent is filed - not when the drug hits the market. Most drugs take 10 to 15 years to go from lab to pharmacy shelf. That means by the time the drug is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the U.S. agency responsible for approving drugs for sale, the patent might only have 5 to 8 years left. That’s not enough time to recoup the $2.3 billion average cost to develop a new drug.

That’s why companies can ask for a Patent Term Extension (PTE) a legal adjustment that adds time to a patent based on FDA review delays. The law allows up to 5 extra years, but the total protected time after FDA approval can’t go beyond 14 years. So if a drug gets approved 12 years after the patent was filed, the company might get 2 years added back. It’s not automatic - they have to apply, prove delays were caused by the FDA, and jump through legal hoops.

Not all patents are equal. A composition of matter patent - which covers the actual chemical structure - is the strongest. But most companies file secondary patents too: for how the drug is formulated, how it’s taken, or what condition it treats. These are easier to get but weaker in court. The FTC found that 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary patents, not the core invention.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Gatekeeper

Market exclusivity is completely different. It’s not about invention. It’s about data. The FDA the regulatory body that evaluates clinical trial data for drug safety and effectiveness doesn’t let generic companies copy your clinical trial results. If you spent $500 million and 8 years running trials to prove your drug works, the FDA won’t approve a cheaper version that just says, "I’ll use their data."

This is called data exclusivity. It’s automatic. No application needed. Just submit your drug for approval, and if you meet the criteria, the FDA locks out competitors for a set period. The length? It depends on the drug.

- New Chemical Entity (NCE): 5 years - no generic can even file an application during this time.

- Orphan Drug: 7 years - for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 U.S. patients).

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity - if the company studies the drug in children.

- Biologics: 12 years - thanks to the 2009 BPCIA law, which treats complex biological drugs differently from chemical pills.

- First Generic: 180 days - if a generic company challenges a patent and wins, they get a head start on the market.

Here’s the kicker: market exclusivity doesn’t care if the drug is new. It cares if you submitted new clinical data. That’s why colchicine a centuries-old drug used for gout got 10 years of exclusivity in 2010. Mutual Pharmaceutical didn’t invent it - they just ran new trials to prove it worked for a different use. The FDA approved it, and suddenly, a 10-cent pill became a $5 tablet. No patent. Just exclusivity.

They Don’t Always Overlap - And That’s the Problem

Many people think patents and exclusivity go hand-in-hand. They don’t. The FDA analyzed 2021 data and found:

- 27.8% of branded drugs had both patent and exclusivity

- 38.4% had patents but no exclusivity

- 5.2% had exclusivity but no patent

- 28.6% had neither

That last one? Drugs that are old, off-patent, and still protected - often because they’re reformulated or repurposed. And the 5.2% with exclusivity but no patent? That’s where things get controversial. These are drugs that never had a strong patent, but the FDA still blocked generics for years. The Congressional Research Service found that 78% of those drugs still had no generic competition during their exclusivity period.

It’s not just about fairness. It’s about money. A single 180-day exclusivity period for the first generic can be worth $100 million to $500 million in extra revenue. The 6-month pediatric extension has generated over $15 billion since 1997. And biologics with 12 years of exclusivity? That’s a $10 billion revenue shield.

What Happens When They Clash?

Imagine this: Your drug’s patent expires. You expect generics to flood the market. But the FDA still has a 3-year exclusivity clock ticking because you submitted new data for a new dosage form. The generics can’t file. The price stays high. This happened with Trintellix an antidepressant drug. Teva Pharmaceuticals waited until 2024 to launch a generic - three years after the patent expired - because of regulatory exclusivity. They lost an estimated $320 million.

Small biotech companies often get burned. A 2022 survey by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization found that 43% of them mistakenly thought patent protection meant market exclusivity. They didn’t apply for FDA exclusivity - and lost years of revenue.

And the FDA isn’t perfect. A 2023 analysis found that 22% of drug companies failed to claim all the exclusivity they were entitled to. That’s an average of 1.3 years of lost protection per product. That’s money left on the table.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The rules are shifting. The FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard a public tool tracking all exclusivity periods for approved drugs in September 2023. Now, anyone can see when a drug’s exclusivity expires - and plan accordingly.

The PREVAIL Act of 2023 proposes cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. The World Trade Organization is debating whether to waive exclusivity for more drugs beyond COVID-19 vaccines. And by 2027, McKinsey predicts that regulatory exclusivity will account for 52% of total market protection time - more than patents.

For generic manufacturers, this means more competition. For patients, it could mean lower prices. For drugmakers? It means they can’t rely on patents alone anymore. They need both.

Why This Matters to You

If you’re a patient, you care about when your prescription gets cheaper. If you’re a pharmacist, you care about when generics arrive. If you’re a student, investor, or policymaker - you need to understand that drug pricing isn’t just about patents. It’s about two systems working in parallel.

Patents protect invention. Market exclusivity protects data. One comes from the patent office. The other from the FDA. One can be challenged in court. The other can’t - because the FDA enforces it automatically.

And if you think a drug’s price is high because of a patent? Maybe. But maybe it’s because the FDA hasn’t let a generic in yet - even though the patent expired. That’s market exclusivity at work.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. A drug can have market exclusivity even if it has no patent protection. This happens when a company submits new clinical data for an existing drug - for example, to treat a new condition or create a new formulation. The FDA grants exclusivity based on that data, not on whether the drug is novel. The 2010 case of colchicine is a famous example: a 300-year-old drug got 10 years of exclusivity after new trials were submitted, despite having no active patents.

How long does FDA market exclusivity last?

The length varies by drug type: 5 years for a New Chemical Entity (NCE), 7 years for orphan drugs, 12 years for biologics, and 6 months added to existing protections if pediatric studies are done. First generic manufacturers get 180 days of exclusivity if they successfully challenge a patent. These periods are set by law and start on the date the drug is approved by the FDA.

Do patents and market exclusivity always expire at the same time?

No. They operate independently. A patent might expire in year 12, but market exclusivity could last until year 15. Or, a drug might have no patent but still be protected by 5 years of exclusivity. The FDA enforces exclusivity regardless of patent status. That’s why some drugs remain price-protected long after patents have expired.

Why do some drugs have multiple exclusivity periods?

A drug can qualify for more than one type of exclusivity if it meets multiple criteria. For example, a new drug for a rare disease (orphan status) that also contains a new chemical entity (NCE) could get 7 years plus 5 years - but they don’t stack. The longer period wins. Pediatric exclusivity is the exception - it adds 6 months to any existing exclusivity or patent, even if it’s already expired.

Can generic companies launch before exclusivity expires?

No - not legally. The FDA is required to block approval of any generic application during a valid exclusivity period. Even if a patent has expired, the FDA will not approve a generic until exclusivity ends. Companies that try to launch early risk lawsuits and fines. The only exception is the 180-day exclusivity for the first generic to challenge a patent - but that’s still a form of exclusivity, not a loophole.

What’s the Orange Book, and how does it relate to exclusivity?

The FDA’s Orange Book lists approved drug products along with their patent and exclusivity information. It’s the official public record used by generic manufacturers to know when they can file applications. However, the Orange Book only lists patents the brand company believes could be infringed - not all patents they hold. Exclusivity periods are also listed, but they’re not always accurate or complete. Companies sometimes fail to claim all available exclusivity, and the FDA doesn’t always catch it.

Final Takeaway

Patent exclusivity is about invention. Market exclusivity is about data. One is enforced by courts. The other by the FDA. One can be challenged. The other can’t. And in today’s pharmaceutical world, market exclusivity is becoming just as important - if not more - than patents.

If you’re trying to understand why a drug stays expensive, don’t just look at the patent. Look at the exclusivity clock. Because sometimes, the real barrier isn’t a patent - it’s a rule the FDA quietly enforces.

Alex Ogle

February 7, 2026 AT 15:11So let me get this straight - a 300-year-old drug like colchicine gets 10 years of exclusivity just because someone ran new trials on it? That’s not innovation, that’s regulatory arbitrage. I get that companies need to recoup costs, but this feels like gaming the system. You don’t invent the wheel, you just polish the spokes and call it a Tesla. The FDA’s rules here are too loose. There’s zero moral high ground in turning a 10-cent pill into a $5 one just because you jumped through bureaucratic hoops. And don’t even get me started on how many of these ‘new uses’ are just repackaged old side effects.

It’s not about patents anymore. It’s about who can afford to hire the best regulatory lawyers. The system’s rigged to reward paperwork, not science.

And yet, we wonder why healthcare costs are out of control.

It’s not rocket science. It’s regulatory theater.

Lyle Whyatt

February 9, 2026 AT 00:19Man, I’ve been in pharma for 15 years, and this post nails it. People think patents are the only barrier - nah. Market exclusivity is the silent killer. I worked on a biologic once - 12 years of exclusivity, zero patents that could be challenged. Generic makers couldn’t even file until year 12. Meanwhile, the brand company kept tweaking the delivery system - new pump, new dosing schedule - each time getting another 3-year exclusivity bump.

It’s not fraud. It’s legal. And that’s worse.

The Orange Book? Half the time it’s outdated. Companies forget to list exclusivity, or the FDA misses it. I’ve seen drugs with 18 months of unclaimed pediatric extension just sitting there. Money left on the table. All because no one at Big Pharma bothered to check the checklist.

And the 180-day first-generic window? That’s where the real money is. One company I know made $400M in 6 months because they challenged a weak patent. The rest of the market? Still waiting.

Regulation isn’t the enemy. Inconsistency is.

MANI V

February 9, 2026 AT 17:57Let me be clear: this entire system is a scam engineered by corporate lawyers and complicit regulators. You call it 'market exclusivity'? I call it legalized theft. A company spends $2 billion to develop a drug - sure. But then they sit on it for 10 years while the public pays inflated prices, all while the FDA hands them extra years like candy? And then they wonder why people can’t afford insulin?

Colchicine? A 300-year-old remedy. A $5 tablet. This isn’t innovation. This is extortion. The FDA should not be a profit multiplier for pharmaceutical CEOs. They’re supposed to protect public health - not turn public trust into a revenue stream.

And don’t give me that 'but they need incentives' nonsense. If you need 12 years of exclusivity to make a profit, your business model is broken. The system rewards greed, not healing.

And yes - I’m angry. You should be too.

Susan Kwan

February 10, 2026 AT 08:57Random Guy

February 10, 2026 AT 11:44Tasha Lake

February 11, 2026 AT 19:42Okay, I’m a grad student in pharmacoeconomics, and I’ve been digging into this for my thesis. The real kicker? Pediatric exclusivity is the most under-discussed tool in the whole arsenal. It’s not just about kids - it’s a strategic extension. Companies get 6 months added to *any* existing exclusivity or patent. So if a drug’s patent expires in 2026, but they do pediatric studies in 2025? Boom - now it’s protected until 2026.5.

And here’s the twist: most pediatric studies aren’t done because it’s medically necessary - they’re done because it’s profitable. The FDA doesn’t require clinical benefit in children - just data collection. So you get drugs tested on kids just to buy more time.

It’s not evil. It’s rational. And that’s why it’s so insidious.

Also - the 180-day first-generic window? That’s why we have ‘patent ambushes.’ Companies file 20+ weak patents just to trigger the clock. One generic challenger wins - gets 180 days - then the whole market floods. But until then? Price stays high. It’s a legal cartel.

Andy Cortez

February 13, 2026 AT 03:07Y’all are missing the forest for the trees. The whole point of exclusivity isn’t to make drugs expensive - it’s to make them *available*. Without exclusivity, no one would invest $2.3B in R&D. You think Pfizer just woke up one day and said, ‘Hey, let’s make a COVID vaccine!’? Nah. They did it because they knew they’d have a window to recoup costs. Same with orphan drugs - without 7 years of exclusivity, no company would touch a disease affecting 50,000 people.

Yes, some companies abuse it. Colchicine? Yeah, sketchy. But the system works 90% of the time. Without exclusivity, we’d have zero new drugs. Zero. And then what? You want to live in a world where every pill is a 1950s generic? I’d rather pay $5 for a new cancer drug than $0.10 for a 1970s version that doesn’t work.

It’s not perfect. But it’s the least-bad option we’ve got. And before you scream ‘corporate greed,’ ask yourself: who funded the drug that saved your cousin? Was it the government? Or a company betting its entire future on science?

Don’t kill the goose. Just make it lay better eggs.

Jacob den Hollander

February 13, 2026 AT 12:59As someone who’s watched a family member wait 3 years for a generic after their patent expired - I just want to say: thank you for explaining this so clearly.

I didn’t realize market exclusivity could block generics even after patents expired. That’s wild. I thought the patent was the only thing that mattered. Turns out, it’s the FDA’s hidden hand keeping prices high.

And the part about colchicine? That broke my heart. My mom took that drug for gout. She paid $400/month for 2 years. I found out later it was basically a 10-cent pill. That’s not capitalism. That’s cruelty dressed up as regulation.

I’m not anti-pharma. I’m anti-gaming. If you’re not innovating, you shouldn’t be rewarded. But right now, the system rewards lawyers more than lab coats.

Let’s fix this. Not with rage - with reform.

Andrew Jackson

February 13, 2026 AT 17:43It is a matter of profound national concern that the United States, the world's foremost innovator in pharmaceutical science, permits a regulatory apparatus to be manipulated by foreign entities and domestic opportunists alike. The very notion that a drug developed in 1723 - yes, 1723 - may be granted a decade of market exclusivity on the basis of a single clinical trial conducted by a corporation with no original intellectual contribution is an affront to the principles of merit, innovation, and American exceptionalism.

Patents are the bedrock of property rights. Exclusivity, as currently administered, is a bureaucratic fiction - a loophole exploited by those who would rather manipulate the system than create value.

When a nation allows its regulatory agencies to grant monopolies on ancient compounds, it betrays its duty to protect the sanctity of invention. The FDA is not a corporate incubator. It is a public trust. And it is failing - spectacularly - in its obligation to the American people.

It is time for Congress to act. Not with compromises. Not with tweaks. But with a full-scale dismantling of the current exclusivity framework - and the establishment of a system grounded in true innovation, not regulatory arbitrage.

PAUL MCQUEEN

February 15, 2026 AT 17:36