Palliative Care Balance Calculator

How Balanced is Your Care?

This tool helps you assess the balance between symptom relief and side effects for palliative care treatments. Based on recommendations from the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care guidelines.

--

When someone is living with a serious illness, the goal shifts from curing to comforting. That’s where palliative care comes in. It’s not about giving up. It’s about making sure the person feels as well as possible - physically, emotionally, and spiritually - no matter how far the illness has progressed. Hospice care is a part of that, focused on the final months when curative treatments are no longer the priority. But here’s the hard part: the medicines that ease pain, shortness of breath, or nausea often come with their own problems - drowsiness, confusion, constipation, even loss of awareness. Finding the right balance isn’t guesswork. It’s a careful, ongoing process, guided by evidence, experience, and deep listening.

What Palliative Care Really Means

Palliative care isn’t just for people who are dying. It’s for anyone with a serious illness - cancer, heart failure, COPD, dementia - at any stage. The goal? Reduce suffering. That means tackling pain, nausea, fatigue, anxiety, and even the feeling of being a burden. It’s not just drugs. It’s talking with families, helping with daily tasks, connecting people to spiritual support, and making sure care aligns with what matters most to the patient. The National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care’s 2018 guidelines outline eight key areas, from physical comfort to emotional and spiritual well-being. These aren’t just suggestions. They’re the standard used by 89% of U.S. palliative programs.

Many people think hospice and palliative care are the same. They’re not. Hospice is a type of palliative care, specifically for those with six months or less to live who’ve chosen to stop curative treatment. Palliative care can start the day someone gets a diagnosis and continue alongside chemotherapy, dialysis, or surgery. The difference? Timing. The goal? Always comfort.

Managing Pain Without Over-Sedating

Pain is the most common reason people seek palliative care. But treating it isn’t as simple as handing out opioids. The NHS North West guidelines say you must assess every pain type individually - location, type (sharp, dull, burning), what makes it worse or better, and how it affects daily life. Many patients have more than one kind of pain. Treating them the same way leads to under- or over-treatment.

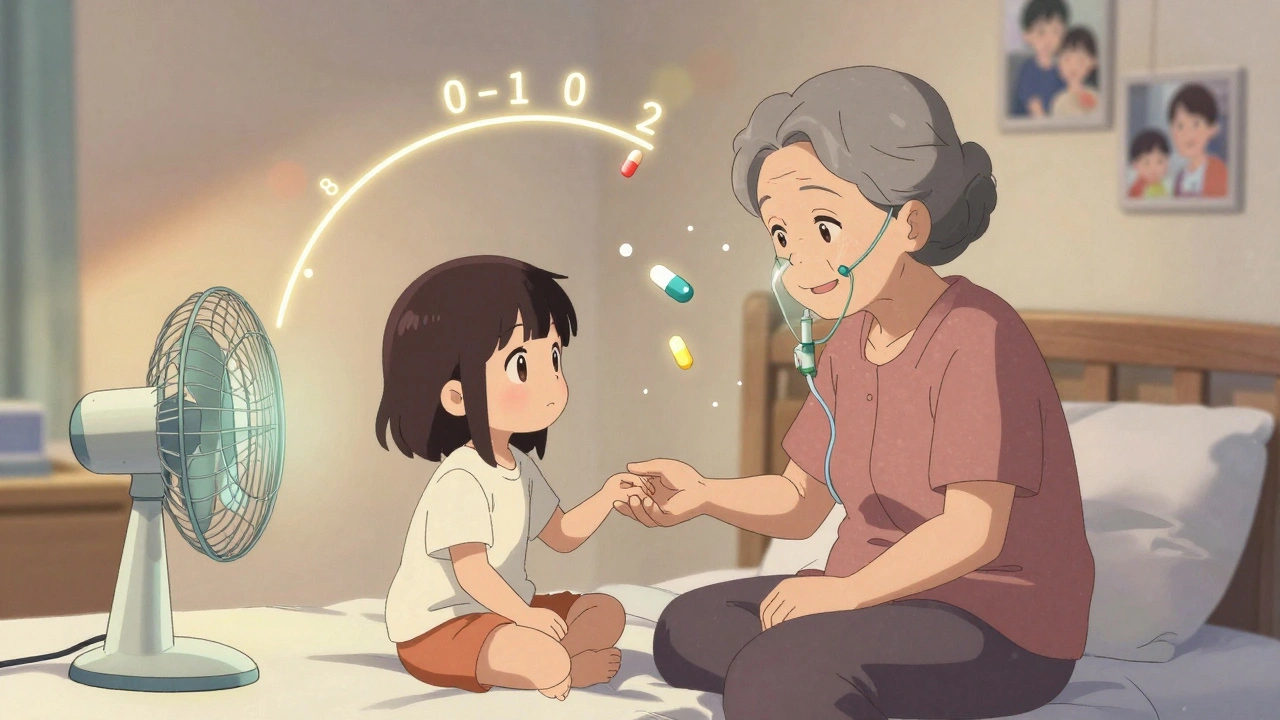

The standard tool? A 0-to-10 scale. Zero is no pain. Ten is the worst imaginable. But numbers alone aren’t enough. A body diagram helps patients point to where it hurts. One study found this method improved communication by 31%. That’s huge. When patients feel heard, they’re more likely to trust the treatment plan.

Opioids like morphine and oxycodone are first-line for moderate to severe pain. But they can cause drowsiness, constipation, and confusion - especially in older adults or those with kidney issues. The key is starting low and going slow. A 2022 survey found 87% of general practitioners don’t know how to adjust opioid doses for kidney problems. That’s dangerous. Palliative care teams use tools like the Dana-Farber ‘Pink Book’ to guide dosing based on organ function. Regular reassessment is non-negotiable. If a patient is sleeping through the day, the dose is too high. If they’re still grimacing, it’s too low. There’s no magic number. It’s about finding the lowest dose that brings comfort.

Shortness of Breath: More Than Just Oxygen

Feeling like you can’t catch your breath is terrifying. It’s not just about low oxygen. It’s anxiety, muscle tension, and the feeling of helplessness. Oxygen can help, but it doesn’t always fix it. The American Academy of Family Physicians gives opioids a ‘B’ level of evidence for easing breathlessness at the end of life. That means strong support. Morphine, even in small doses, can calm the brain’s panic response to breathlessness without making someone sleepy.

Non-drug methods matter too. A fan blowing gently on the face, sitting upright, breathing techniques, and calming music all help. One study showed combining a fan with low-dose morphine reduced breathlessness more than either alone. The trick? Don’t wait until the person is gasping. Start early. Ask: ‘On a scale of 0 to 10, how bad is your breathlessness right now?’ Then check again in 30 minutes after treatment. If it drops to a 3 or 4, you’ve done your job.

Delirium: When the Mind Gets Unsteady

Delirium - sudden confusion, agitation, hallucinations - affects up to 80% of people in their final days. It’s not dementia. It’s a medical emergency. Causes? Infection, dehydration, medication side effects, or organ failure. The UPenn Comfort Care Guidelines say you must check for it every 12 hours using the CAM-ICU tool and score agitation every 4 hours with the RASS scale. If someone is restless or combative, don’t assume it’s ‘just old age.’

Haloperidol is the first-line treatment. But it’s not a sedative. It’s an antipsychotic. The goal isn’t to knock them out. It’s to quiet the brain’s chaos. Doses are tiny - often just 0.5 mg. Too much can make someone stiff or slow their breathing. And here’s the rule: once the person is calm, you stop the drug. Not because it’s bad, but because it’s no longer needed. Many hospitals now use electronic alerts to remind staff to reassess delirium daily. That’s cut unnecessary drug use by 40% in some units.

Constipation and Nausea: The Hidden Side Effects

Almost everyone on opioids gets constipated. It doesn’t go away. You can’t just wait for it to clear up. Prophylactic laxatives - like senna or polyethylene glycol - are started on day one. No exceptions. If you wait until the patient is bloated and in pain, it’s harder to fix. The same goes for nausea. Metoclopramide or ondansetron are common, but sometimes the real fix is changing the opioid. Switching from morphine to hydromorphone can cut nausea by half in some patients.

For bowel obstruction - when the gut stops moving - steroids like dexamethasone are preferred over octreotide. The AAFP says octreotide has ‘limited benefit.’ Steroids reduce swelling and can get things moving again. But they can raise blood sugar. So you monitor. You don’t just give and forget.

When Medications Cause More Problems Than They Solve

It’s easy to keep adding drugs to fix side effects. A patient gets drowsy from morphine, so you give stimulants. They get constipated, so you give laxatives. Then they get confused from the laxatives, so you give antipsychotics. It’s a chain reaction. The best palliative care teams do the opposite. They step back. Ask: ‘What’s the real problem? Is this drug helping more than it hurts?’

One nurse in Manchester told me about a woman with advanced lung cancer who was so sedated she couldn’t talk to her grandchildren. The family insisted the morphine stay. But when the team reduced the dose by 30% and added a fan for breathlessness, the woman was alert again. She held her granddaughter’s hand for the first time in weeks. That’s the balance. Not more drugs. Better choices.

What Families Need to Know

Families often fear giving too much pain medicine. They think it’s ‘killing’ their loved one. That’s not true. The goal isn’t to make someone unconscious. It’s to make them comfortable enough to be present. The NCHPC guidelines say families have the right to help their loved one die free of pain - with dignity. That’s not giving up. That’s loving deeply.

One of the biggest barriers? Time. Nurses report 68% don’t have enough time to complete full symptom assessments. Documentation takes hours. A 2022 Fraser Health survey found 43% of staff felt buried in paperwork. That’s why tools like digital symptom trackers are being rolled out. In pilot programs, they’ve improved symptom control by 18%. Less writing. More time with patients.

The Future: Less Medication, More Precision

The field is changing. In 2023, Fraser Health added guidance on medical cannabis. One study showed it cut opioid use by 37% in some patients. But it caused dizziness in 29%. So it’s not a magic bullet. It’s another tool.

Research is also looking at genetics. A 2022 JAMA study found certain gene variants predict how someone will respond to opioids. In five years, a simple blood test might tell a doctor: ‘This patient needs half the usual dose.’ That’s precision palliative care.

Tele-palliative care is growing fast. Right now, 55% of rural counties in the U.S. have no palliative services. By 2027, telehealth could reach 40% of those patients. That’s life-changing for people who can’t travel.

The biggest challenge? There aren’t enough trained specialists. Only 7,000 certified palliative doctors exist in the U.S. for a need of 22,000. That’s why every doctor, nurse, and social worker should know the basics. You don’t need to be an expert to ask: ‘On a scale of 0 to 10, how’s your pain?’

Getting Started: What You Can Do Today

- Use the 0-10 pain scale every time you check in.

- Start laxatives on day one of opioid use - don’t wait.

- Use a fan for breathlessness. It’s free, safe, and works.

- Ask: ‘Is this drug helping more than it’s hurting?’

- Listen more than you talk. Sometimes, the answer is in the silence.

Palliative care isn’t about fixing what can’t be fixed. It’s about holding space for what matters most - comfort, connection, and dignity. The right balance isn’t found in a textbook. It’s found in the quiet moments between a patient and the person who refuses to look away.

Is hospice care only for people who are dying?

Hospice care is specifically for people with a prognosis of six months or less who have chosen to stop curative treatment. But palliative care - which includes comfort-focused symptom management - can start at any point during a serious illness and can be given alongside treatments meant to cure. Many patients benefit from starting palliative care early, even while undergoing chemotherapy or surgery.

Do opioids shorten life when used for pain relief?

No. When used properly in palliative care, opioids do not shorten life. The goal is to relieve suffering, not to cause sedation or hasten death. Studies show that well-managed pain control improves quality of life without affecting survival. Fear of addiction or overdose often leads to undertreatment, which causes more harm than the medication itself.

Why do some patients become confused on pain medications?

Confusion, or delirium, can happen due to opioid buildup, especially in older adults or those with kidney problems. It can also be caused by dehydration, infection, or other medications. Regular assessments using tools like RASS and CAM-ICU help spot it early. Often, reducing the opioid dose or switching to a different one clears it up without needing sedatives.

Can non-drug methods really help with symptoms?

Yes. A gentle fan for breathlessness, music therapy for anxiety, repositioning for pain, and holding hands for comfort all have proven benefits. These methods reduce the need for higher drug doses. In fact, combining a fan with low-dose morphine works better than morphine alone for breathlessness. Non-drug approaches are safe, low-cost, and often more meaningful to patients.

What should families do if they think their loved one is being over-medicated?

Ask for a care review. Request to speak with the palliative care team and ask: ‘Is this medication still helping?’ or ‘Could we try lowering the dose?’ Many families worry they’re being selfish for asking, but the goal of palliative care is to keep the person alert and present as long as possible. If they’re sleeping all day and can’t talk, the dose may be too high. Don’t be afraid to speak up.

Taya Rtichsheva

December 8, 2025 AT 14:48fan works tho. i blew one on her face and she smiled. weird but true.

Gilbert Lacasandile

December 9, 2025 AT 04:44Haley P Law

December 9, 2025 AT 13:17Also-fan. Always a fan.

Chris Marel

December 9, 2025 AT 14:49Nikhil Pattni

December 11, 2025 AT 11:59Arun Kumar Raut

December 12, 2025 AT 07:22precious amzy

December 13, 2025 AT 02:17Carina M

December 15, 2025 AT 01:21William Umstattd

December 15, 2025 AT 06:42Tejas Bubane

December 16, 2025 AT 17:20Ajit Kumar Singh

December 17, 2025 AT 00:34Maria Elisha

December 17, 2025 AT 08:57