When your liver fails, there’s no backup system. No reset button. No pill that can replace what it does-filtering toxins, making proteins, storing energy, regulating blood sugar. If it’s gone, you need a new one. That’s where liver transplantation comes in. It’s not just a surgery. It’s a second chance. But it’s not simple. It’s not quick. And it’s not for everyone.

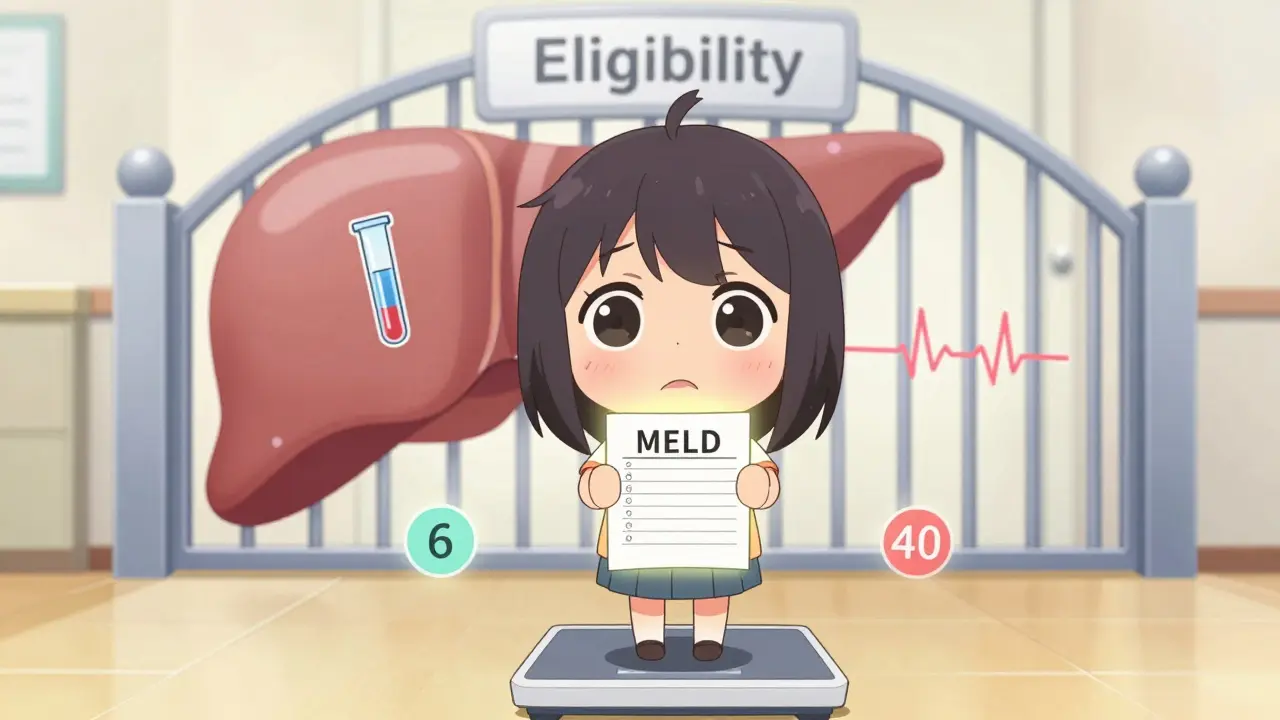

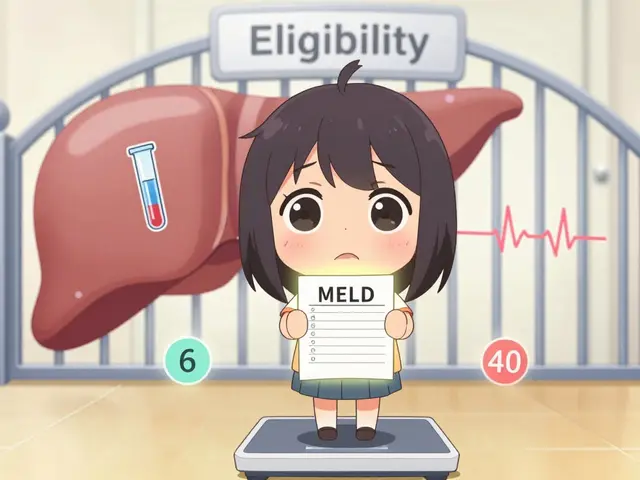

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The decision isn’t based on how sick you feel. It’s based on numbers-cold, hard data. The MELD score (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) is the gatekeeper. It uses blood tests for bilirubin, creatinine, and INR to predict your risk of dying in the next three months. A score of 6 means you’re not in immediate danger. A score of 40? You’re at the top of the list. The higher your MELD, the sooner you get called. But numbers aren’t everything. If you’re still drinking alcohol or using drugs, you’re not eligible. Most centers require at least six months of sobriety. Some, like those following newer research, are starting to question that rule. One 2023 study showed patients with three months of abstinence had nearly the same survival rates as those who waited six. But policies haven’t caught up everywhere. Some centers still turn people away based on outdated guidelines. Cancer changes the game. If you have hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), you have to meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor’s bigger or has invaded veins, you’re usually out-unless you get special review. And if your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood marker is over 1,000 and doesn’t drop below 500 after treatment, you’re typically not considered. Then there’s the psychosocial side. Do you have someone to help you after surgery? Do you live in a safe place? Can you afford to take time off work? Do you understand how to take your pills every single day? If the answer is no to any of these, you might be denied-even if your liver is failing. A social worker, a psychologist, and your hepatologist all sign off before you get on the list.The Surgery: What Happens in the Operating Room

A liver transplant isn’t a quick procedure. It takes between six and twelve hours. The surgeon removes your damaged liver, waits for the new one to arrive, and then sews it in. There are three phases: first, removing your liver (hepatectomy). Then, the anhepatic phase-where you have no liver at all. Your body survives on machines that take over its job for a few hours. Finally, the new liver is connected to your blood vessels and bile ducts. Most transplants use the “piggyback” technique. Instead of removing the large vein behind the liver (the inferior vena cava), the surgeon keeps it and attaches the new liver to it. This reduces blood loss and complications. About 85% of transplants use this method. For living donors, things get more complex. A healthy person-usually a family member or close friend-gives up part of their liver. For adults, surgeons take the right lobe, which is about 55-70% of the liver. For children, they take the left lateral segment. The donor’s liver regrows to nearly full size in a few months. The recipient’s liver also regenerates. That’s one of the liver’s most amazing tricks. Donors must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and be free of liver, heart, or kidney disease. They can’t smoke, drink, or use drugs. The remnant liver left in the donor must be at least 35% of the original volume. The graft-to-recipient weight ratio must be at least 0.8%. If those numbers aren’t right, the surgery won’t happen.

Living vs. Deceased Donors: The Trade-Offs

Waiting for a deceased donor can take months-or years. In high-MELD patients, the average wait in California is 18 months. In the Midwest, it’s 8. That’s a huge difference. Living donor transplants cut that wait to about three months. But it’s not risk-free. Donors face a 0.2% chance of dying during surgery. About 20-30% have complications: bile leaks, infections, or pain that lasts months. Some donors say they regret it. Others say it was the best thing they ever did. The decision isn’t just medical-it’s emotional. Deceased donor livers come from two sources: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). DCD livers used to be considered risky. They had higher rates of bile duct problems-25% versus 15% for DBD. But new tech is changing that. Machines that keep the liver alive and beating outside the body (machine perfusion) have cut those complications down to 18%. That’s a 28% improvement. Now, DCD livers are being used more often-12% of all transplants in 2022.Life After Transplant: The Immunosuppression Lifeline

Your body will try to kill the new liver. It doesn’t know it’s supposed to accept it. That’s why you need immunosuppressants-for the rest of your life. The standard combo is three drugs: tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. It keeps your immune system from attacking the liver. Doctors aim for a blood level of 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then lower it to 4-8 ng/mL. Too high? You risk kidney damage, tremors, or diabetes. Too low? Rejection. Mycophenolate stops white blood cells from multiplying. It can cause nausea, diarrhea, or low blood counts. Prednisone, a steroid, reduces inflammation. But it causes weight gain, bone loss, and high blood sugar. That’s why 45% of U.S. transplant centers now skip prednisone after the first month. They call it “steroid-sparing.” It cuts diabetes risk from 28% to 17%. About 15% of patients have acute rejection in the first year. It’s often caught early through blood tests. If your bilirubin spikes or your liver enzymes go up, you get a biopsy. Most cases are fixed by tweaking tacrolimus or adding sirolimus. Long-term, side effects pile up. One in three patients develop kidney problems from tacrolimus. One in four get diabetes. One in five have nerve issues like shaking or headaches. Mycophenolate causes stomach problems in 30% of people. You’ll need blood tests every week for three months, then every two weeks, then monthly. After a year, quarterly checks are enough. Medication costs? Around $25,000 to $30,000 a year-just for the pills. Insurance doesn’t always cover everything. Many patients struggle to pay. Some skip doses. That’s dangerous. Compliance has to be above 95%. One missed dose can trigger rejection.

What You Need to Know Before and After

Getting on the list isn’t easy. The evaluation takes 3-6 months. You’ll do cardiac stress tests, lung function tests, CT scans, and psychiatric evaluations. You’ll meet with nutritionists, social workers, and financial counselors. You need to prove you can handle the long haul. After surgery, you’re in the hospital for 14-21 days. You’ll be on oxygen, IV lines, and monitors. You’ll learn how to check your temperature, weight, and blood pressure. You’ll memorize the names of your pills. You’ll learn to spot signs of rejection: fever over 100.4°F, yellow skin, dark urine, extreme fatigue. Infection is another big risk. You can’t go to crowded places. You can’t clean cat litter. You can’t eat raw sushi. You’ll need vaccines-flu, pneumonia, hepatitis A and B. But you can’t get live vaccines like measles or shingles. The best outcomes come from centers with dedicated transplant coordinators. These are nurses or social workers who follow you every step of the way. Centers with them see 87% one-year survival. Without them, it’s 82%.What’s Changing in Liver Transplantation?

New rules are coming. The AASLD is updating guidelines to allow donors with controlled high blood pressure and BMI up to 32. That’s a big shift. It means more people can donate-and more people can get transplants. In British Columbia, they’ve changed how they handle alcohol-related liver disease. Instead of a strict six-month rule, they now include cultural support and community ties in their evaluation. For Indigenous patients, this matters. It’s not just about sobriety-it’s about healing in a way that fits their life. Portable liver perfusion devices are now FDA-approved. They keep donor livers alive for up to 24 hours instead of 12. That gives surgeons more time to match donors with recipients. It also helps livers that were once considered “marginal” survive and work well. And there’s hope for the future. Some kids are now being taken off immunosuppression after five years. Researchers are using special immune cells-regulatory T-cells-to teach the body to accept the new liver. If this works in adults, we might one day not need lifelong drugs. But for now, transplant remains the only cure. No artificial liver can keep you alive for more than 30 days. No pill can replace a liver. So if you’re eligible, if you’re ready, and if you have the support-you’re one of the lucky ones. A new liver isn’t just a replacement. It’s a new life.Can you live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes, most people return to normal activities within 6-12 months. Many go back to work, travel, exercise, and even have children. But you’ll always need to take immunosuppressants, attend regular check-ups, and avoid infections. Lifestyle changes are permanent, but they’re manageable.

How long do liver transplants last?

About 70% of transplanted livers are still working five years after surgery. For those who avoid complications like rejection or infection, many last 10-20 years or longer. Some patients have had functioning transplants for over 30 years.

Can you drink alcohol after a liver transplant?

No. Even if your original liver disease wasn’t caused by alcohol, drinking after transplant can damage the new liver. Most centers require lifelong abstinence. Alcohol also interacts dangerously with immunosuppressants and increases the risk of liver damage and cancer.

What happens if your body rejects the new liver?

Acute rejection happens in about 15% of patients in the first year. It’s usually caught early through blood tests and treated by adjusting immunosuppressant doses. Chronic rejection is rarer but harder to treat. If rejection can’t be controlled, another transplant may be needed-but that’s rare and complex.

Are there alternatives to liver transplantation?

For early liver disease, medications, diet changes, and stopping alcohol can help. But once you reach end-stage failure, no other treatment can replace liver function. Artificial liver devices can support you temporarily, but none can keep you alive long-term without a transplant.

Rory Corrigan

January 4, 2026 AT 23:16Connor Hale

January 5, 2026 AT 02:23Charlotte N

January 7, 2026 AT 00:22Catherine HARDY

January 7, 2026 AT 20:01melissa cucic

January 8, 2026 AT 11:08Vikram Sujay

January 10, 2026 AT 05:41Shanna Sung

January 11, 2026 AT 10:42mark etang

January 13, 2026 AT 01:25josh plum

January 14, 2026 AT 18:18John Ross

January 16, 2026 AT 13:26Clint Moser

January 17, 2026 AT 13:14Ashley Viñas

January 19, 2026 AT 10:55Brendan F. Cochran

January 19, 2026 AT 23:50jigisha Patel

January 21, 2026 AT 04:39Connor Hale

January 21, 2026 AT 11:08